Le signore del Nobel (per la chimica 2020)

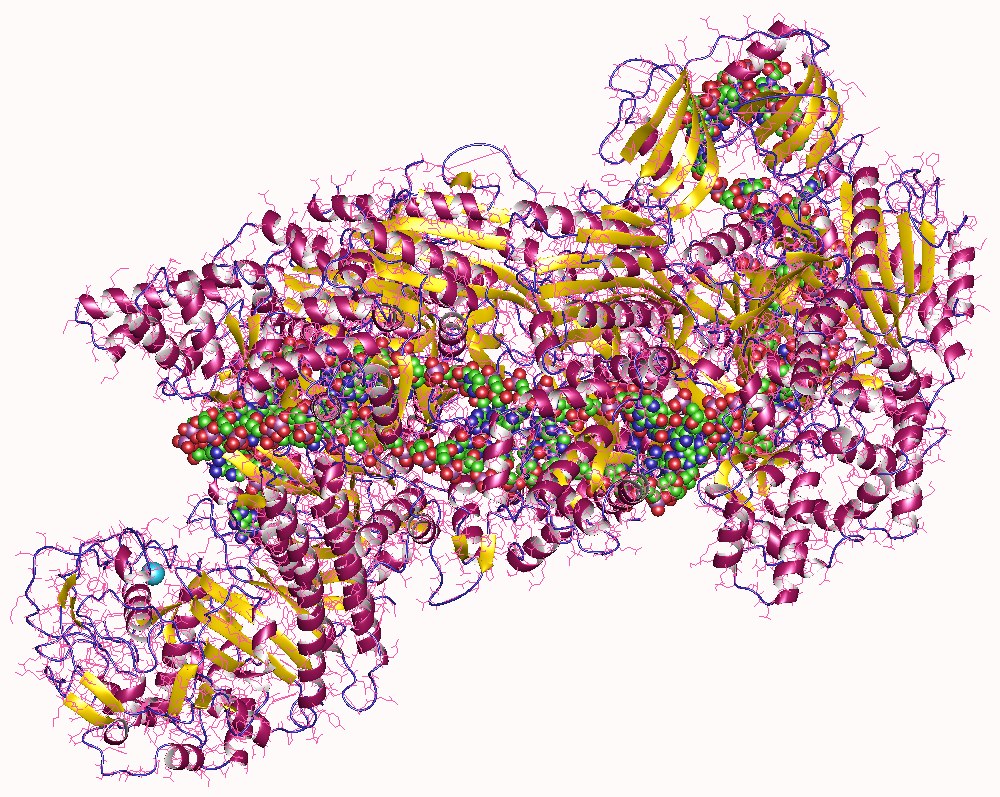

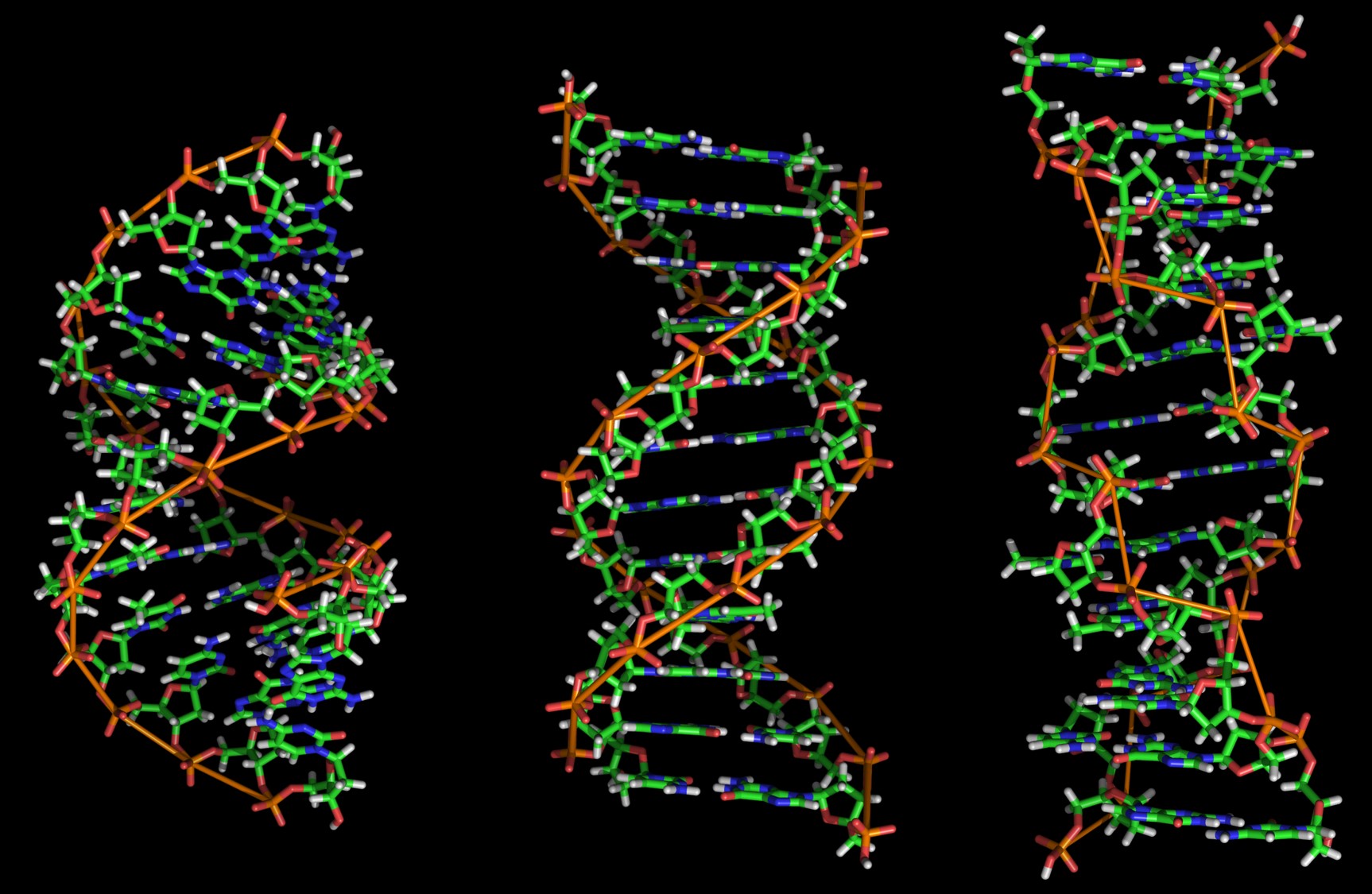

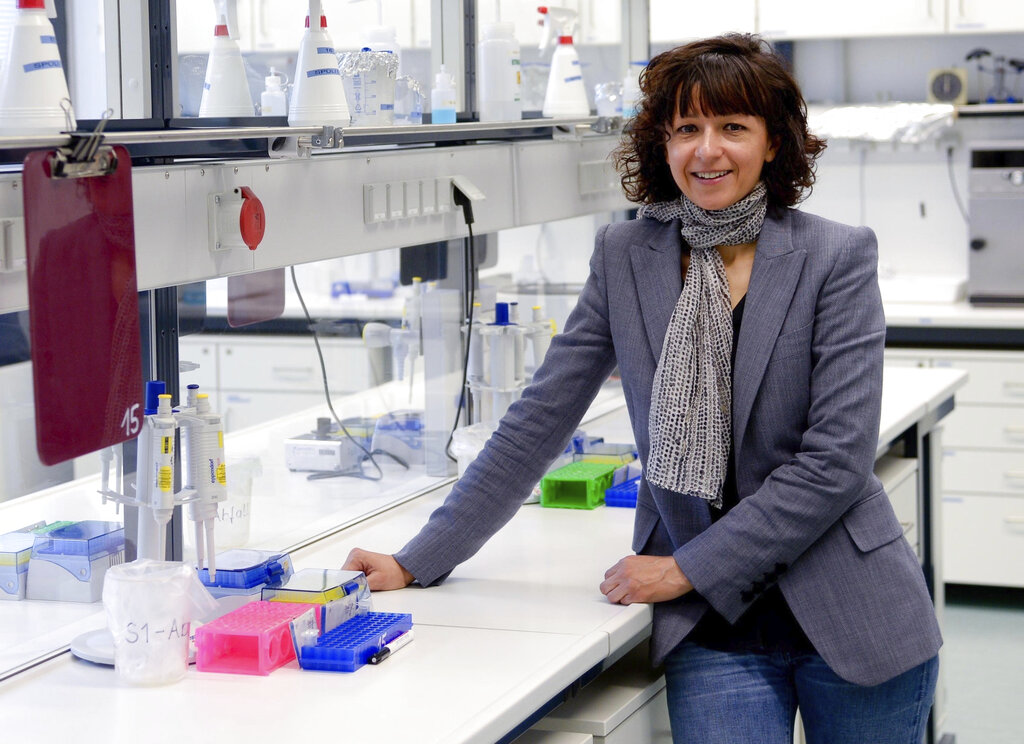

Le scienziate Emmanuelle Charpentier (francese, 51 anni) e Jennifer A. Doudna (statunitense, 56 anni) sono state premiate dall’Accademia svedese per lo sviluppo di un nuovo metodo per la manipolazione del genoma. La tecnica in questione, chiamata Crispr, è di una potenza incredibile («solo l’immaginazione può porre limiti al suo utilizzo» ha scritto l’Accademia) e allo stesso tempo di una semplicità e di una eleganza straordinaria: permette per la prima volta nella storia dell’umanità di modificare a piacimento il Dna contenuto nelle nostre cellule.

Naturalmente, fin dal momento della scoperta, che dal 2015 in poi è stata ulteriormente perfezionata, le ricercatrici stesse si sono rese conto delle problematiche etiche connesse al suo utilizzo. Un tema che occuperà la discussione pubblica nei prossimi anni.

Nel frattempo le due ricercatrici si godono il premio: hanno dimostrato, una volta di più, che non è vero che la ricerca scientifica sia appannaggio soprattutto degli uomini. Qualcuno le ha già chiamate “Le Thelma e Louise del Dna”.